Going cross-platform

December 2025

Porting koi farm 1 to the switch was not easy. The game runs well on it now, at the time of writing the only thing left to port is the interface. What did not help was writing the game in the most unportable mainstream language, JavaScript, so everything has to be rewritten in C++. What also doesn't help is the fact that the entire interface is basically a website, and game consoles aren't browsers, so they can't render it. These seemingly worst case language choices reflect the fact that koi farm was never made to be a game, it was just a small experiment in the browser that got out of hand.

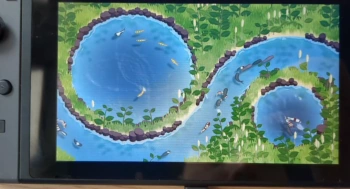

Koi farm 2 however is designed to run on many different platforms, including the Nintendo Switch (2). The game engine is entirely written in portable C++, and it talks to the GPU using Vulkan, which the Switch supports just like Windows and Linux. Unfortunately, when we tried building koi farm 2 for the Switch this month, it did not compile. A few issues had to be resolved first.

- I implemented some classes that took references to static objects in their template, it turns out that was not allowed. Microsoft's compiler does allow it, which led me to assume this was valid C++, but it isn't.

- Many singleton classes were static, and construct before the main function runs. This causes a whole range of issues.

- The filesystem on consoles is very different, and the engine needs to support that.

The game now compiles and runs on our devkit. Rendering doesn't work yet, but we'll probably figure it out very soon, which means koi farm 2 will be Switch compatible from the start. The only difference with PC versions may be slightly lower graphics settings or scene limits (koi and plant counts) to make sure it runs at 60fps, while the PC version allows for very large scenes.

I've been working on adding the procedural plant breeding system, and the gameplay mechanics require a large number of plants in a single scene; there can be thousands of unique koi, but also thousands of plants. One of the bigger challenges is rendering these plants, or rather, not rendering them when they're out of view. The only plants in existence so far are grass patches, and these toggle on or off based on grid cell visibility. For other plants, this can largely be the same. The difference is that grass is everywhere, but custom plants can be sparse. The grass system expects grass for almost every tile, and when a tile has no grass it emits an empty render call. This system will not scale at all, because I'd have to emit an empty render call for every possible plant on a tile, which would result in wasting most GPU resources by forcing it to handle empty commands. Besides, emitting empty calls at all was not very nice to begin with.

A better way to handle this is by compacting draw calls on the GPU. This means the GPU does the following:

- The GPU checks how many visible plants exist on every visible grid cell.

- Then, the GPU calculates the offset of the draw calls produced by each grid cell.

- The GPU iterates over all grid cells again, but instead of checking how many plants exists, it writes the draw calls for those plants to a draw call array. The offset in this array was previously calculated.

- A list of draw calls for all visible plants now exists, and the GPU uses this list to draw a frame.

Steps 1-3 are only executed when the camera moves or when plants are added to or removed from the scene, so for most frames, only step 4 is executed.

This approach to rendering is called GPU driven rendering, and it's an alternative to letting the CPU figure out what's visible and send draw calls to the GPU. The latter is simply not an option for koi farm, because there are too many potentially visible objects in a scene. This might work on a gaming PC and lots of multithreading, but it won't work on simpler computers or tablets, and it definitely won't work on older consoles. The GPU is much better at parallel tasks like iterating over all things and figuring out whether they need to be drawn.

Finally, to optimize rendering a bit more, I'm sorting all grid cells front to back before building the draw lists. This may seem counterintuitive, if you'd draw a painting you'd start with the background and then paint over that. For the GPU it's the other way around: if I draw something like a big rock in the foreground, the depth of that rock is written to the depth buffer, which makes sure that successive draw calls don't overwrite the rock if they're behind it. By drawing the rock first, I'm occluding as many pixels as possible, which prevents them from being calculated and written later. This reduces overdraw: overwriting pixels.

The only information the CPU now needs to prepare each frame is a list of visible grid cells. This used to be simple when the grid was flat, I projected the camera frustum on the flat ground plane and gathered all cells within it (see my post from May). Since last month, this method is no longer accurate because terrain has elevation; the cells are no longer on a flat plane. I'll have to use one of the following new methods:

- I can consider all cells in a scene, and cull them using a more advanced (and slow) height aware method. This doesn't scale well on its own: doubling the amount of grid cells would make it twice as slow. A better way to do this is to create a hierarchy of grid cells. The image shows an example of such a hierarchy, where every four grid cells fall under one higher level grid cell. That way culling works more efficiently. For every highest level grid cell, I check whether it's completely visible, partially visible, or completely invisible.

- If it's completely visible, all cells under it are visible.

- If it's completely invisible, all cells under it are invisible.

- If it's partially visible, I run the algorithm for all four cells one level down.

- I can use the GPU again to check visibility of all cells in parallel. The algorithm above can be used on the GPU as well, but it doesn't parallelize very well so culling each cell individually may be faster.

While the first method feels elegant and will perform well (time complexity is logarithmic instead of quadratic), doing this work on the GPU as well may be better. The list of visible cells is only needed on the GPU after all. Generating it on the CPU and then uploading it to the GPU may be an unnecessary detour, and the CPU has plenty of work to do already.

Because a first batch of game audio will be made in 2026, I've decided to prepare the engine to play sound effects. To give the sound designer as much creative freedom as possible, I've chosen to use Wwise, which is one of the big game audio solutions.